In 1935, Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published a paper concluding that quantum mechanics was an incomplete theory [1]. Their conclusion was based on a ‘thought experiment’ resulting in contradictions. However, it took nearly half a century to transform this ‘thought experiment’ into a real experiment. When it finally happened, the results were a clear victory for quantum mechanics. This paved the way for the 2nd quantum revolution in the 1990s. This post will review the experiment(s) and demonstrate how the observations challenged our worldview.

Einstein did not claim that quantum theory was wrong; he claimed it was incomplete. The argument was that quantum theory predicts a correlation between events over a distance without giving any means to create this correlation. Quantum mechanics does not specify any interaction between the events or communication between the locations where the events take place. Einstein and co-workers concluded that we would need to add something to quantum mechanics to explain what was going on. This addition was given the name ‘hidden variables’ to describe additional information carried by particles or exchanged between particles, which we cannot measure but which does influence the correlation.

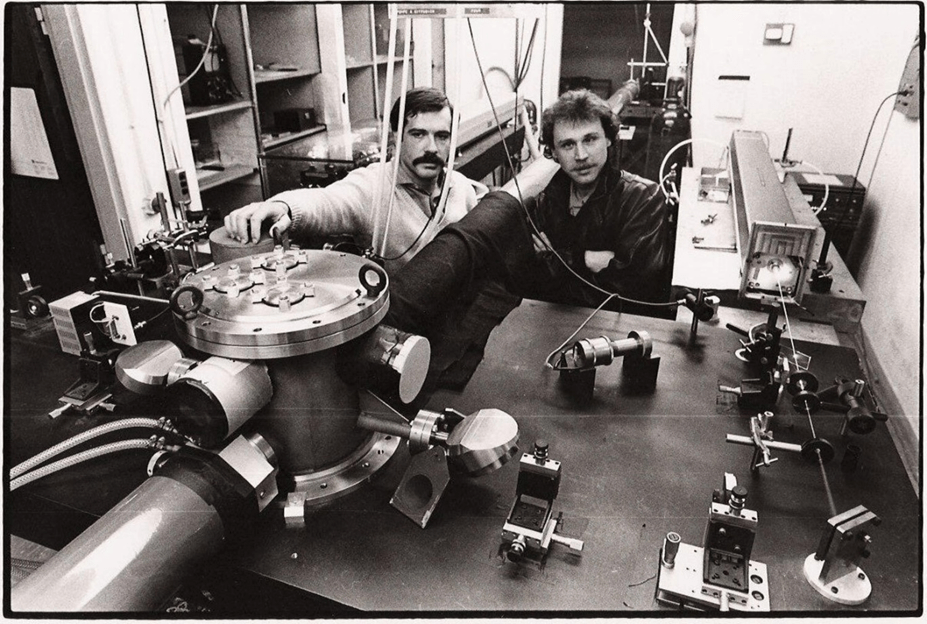

In 1981 and 1982, Alain Aspect published his astonishing experimental results [2,3,4]. At that time, he was undertaking his ‘habilitation’ at the University of Paris-Sud in France. (Habilitation is an advanced academic degree that can be pursued after obtaining a PhD). Alain Aspect observed correlations that are stronger than what can be explained by ‘hidden variables.’ With this result, Einstein’s argument was proven wrong, and the road was opened to a new era of progress in quantum physics.

Alain Aspect based his experiments on the work of John Bell, who, in the 1960s, developed his famous inequalities. Bell’s genius insight was to prove that there is an upper limit to correlations between particles measured at different locations for any theory that excluded ‘spooky action at a distance.’ In his calculations, he started with a model that includes all possible hidden variables and concluded that correlations cannot exceed a specific value. Therefore, if scientists could demonstrate correlations higher than this upper limit, it would settle the debate initiated by Einstein in 1935 once and for all. In a previous post, we used a simple coin game to explain Bell’s argument (the coins in this analogy carry the hidden variables, and the correlation is between players seeing a coin at their side heads up or tails up).

When Alain Aspect began his research, groups in the USA had performed experiments on Bell’s inequalities [5]. Entangled photons had already been observed in the 1940 [6]. John Bell had already proposed that for a foolproof demonstration, he would have to change the orientation of the detectors faster than the time light takes to travel from the source to this detector. This meant he had to switch detectors within 0.01 millionth of a second. None of the other research groups could accomplish this task, so Alain Aspect took up the challenge.

In the early 80s, after more than half a decade of work, Alain Aspect could present the results of his research. The purpose of the experiments was to prove that quantum physics was correct and that, on this particular topic, Einstein was wrong. The outcome of his research was a resounding victory for quantum mechanics. Let’s take a closer look at the experiments and answer the following questions:

- How did they create entangled photons?

- How did they detect the correlations?

- How did they conclude on the violation of Bell’s inequalities?

Creating entangled photons

Entanglement is at the core of quantum mechanics. Erwin Schrödinger called it the defining characteristic that sets quantum theory apart from classical lines of thought. Creating entangled photons is not easy. In the experiments, Aspect used photons that were entangled in their polarization. Let’s first jog our memory on polarization, then look at entanglement and entanglement creation.

Battle ropes

Many fitness enthusiasts use ‘battle ropes’ in the gym to stay fit. By swinging these ropes, we can create waves that travel along them. Depending on how you swing the rope, you can make waves with different polarizations. For instance, swinging the rope up and down creates a vertically polarized wave, whereas swinging left to right produces a horizontally polarized wave. Similarly, you can make circular, elliptical, or diagonally polarized waves. The polarization of light works the same, where the electric field can oscillate in any direction, be it linear, circular, or elliptical.

Entanglement

Now imagine the fitness guy (or girl) holding two ropes. We do not know how the rope is swung, but we do know that for balance, (s)he has to make the same movement with the left and right arm. If one arm is swinging up and down, the other should do the same with the opposite phase (if one arm is going up, the other is going down). If one arm makes circles clockwise, the other arm makes circles counterclockwise. In this analogy, we do not know how one single rope moves, but we know that the two ropes move similarly. For entangled photons, it works the same [7]. We do not know the polarization of any of the photons individually. Still, once we detect the polarization for one photon, we also know precisely the second photon’s polarization.

To create entangled photons, we need a source that emits two photons at the same time. This source should not restrict the polarization of any single photon but only the polarization of both photons combined. If, for instance, the angular momentum (the amount of ‘rotation’) of the source is the same before and after the emission of the two photons, we know that the total angular momentum carried by the photons has to be zero (angular momentum is conserved and if there is no change in the angular momentum of the source the angular momentum of the emitted photons combined should also be zero). This means we do not know the polarization of any of the photons individually, but we do know that if we determine the polarization of one photon, we also know the polarization of the other photon: the photons are entangled.

Entangled photons from calcium atoms

For the experiments in the early 80s, Alain Aspect used Calcium atoms as a source of entangled photons. The atoms can be brought to an ‘excited state’ with lasers (which means an atom picks up energy from the laser). This atom will release the energy later by emitting light. The atom returns to the ‘ground state’ when the energy is released. For the specific case of Calcium, it is possible, by carefully tuning the lasers, to bring the atom in such an excited state that when it returns to the ground state, the energy is released by emitting two photons. The angular momentum of the Calcium atom in the excited state and the ground state is zero, so although we do not know the polarization of the individual photons, we do know that the two photons are entangled.

Detecting correlations

In the three publications, Alain Aspect and team have presented an ever more refined method to measure the polarization of the entangled photons emitted from Calcium atoms.

March 1981

In the first article, Aspect and team reported on their experiment with polarizers as detectors. These polarizers transmit photons polarized in a specific direction but block photons polarized in the orthogonal direction. The team measured the correlation between photon detection for the polarizers angled at different orientations. Specifically, they evaluated the situation where the detectors for both photons were misaligned by 22.5 degrees or 67.5 degrees. The most significant deviation between quantum and classical physics was foreseen for these angles.

December 1981

In the second set-up, they improved the detection of the photons. The team no longer used polarizers that block one polarization direction. They used a polarization splitter, which directs photons with orthogonal polarizations to different detectors. The team placed equipment on rotatable tables such that the orientation of the polarization splitters for both photons could be varied. The advantage of this set-up is that it can detect correlation and anti-correlation (so we also see a signal from the detector when two photons are detected with orthogonal polarization, while in the first set-up, we only see a signal for parallel polarization). The improved set-up enables the use of the CHSH inequality, a variant of Bell’s inequality that is more generically applicable.

September 1982

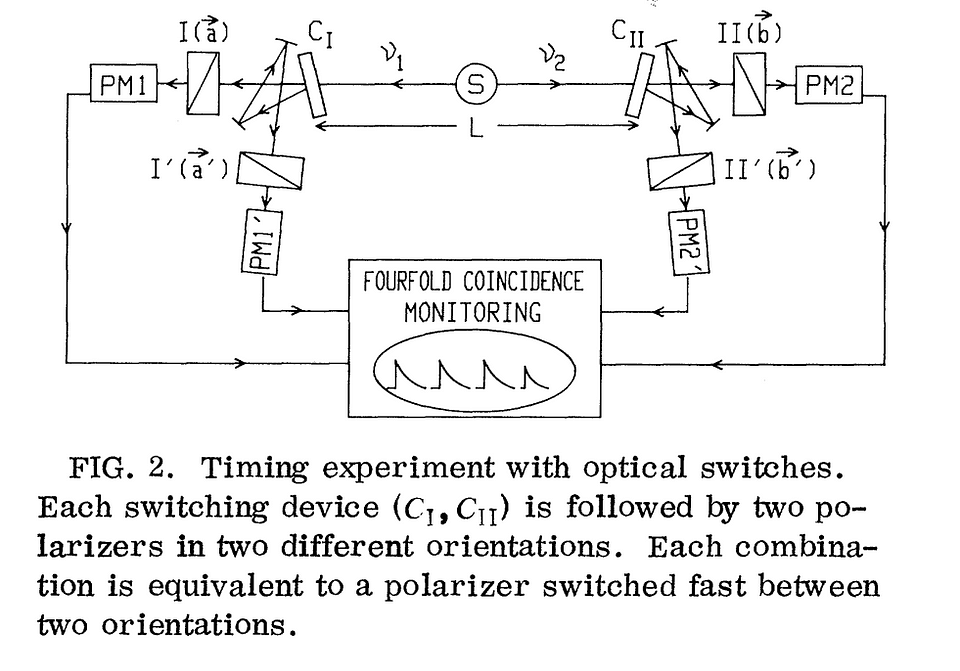

John Bell already foresaw a possible pitfall in empirically verifying his inequalities. If the orientation of the detectors was set long enough before the entangled particles were created, then in principle, the signal could travel back to the photon source and influence the polarization of the photons. Although the mechanism for this signaling would be unknown, the possibility still renders the experimental verification questionable. For this reason, Aspect and team conducted a third experiment on which they reported in 1982, where the polarization splitters could be very rapidly switched. Rather than using mechanically rotating tables, they used acousto-optical switches. These switches operate at speeds of 10 ns (0.01 of a millionth of a second). This is faster than the time it takes photons to travel from the source to the detectors ( around 40ns). This speed enables setting the polarization orientation of the detector after the entangled photons are created. The loophole that John Bell foresaw could thus be closed in this third experiment.

Drawing conclusions

The experiments show correlations between two entangled photons for different polarization orientations at different locations. John Bell’s famous inequalities had already established an upper limit to these correlations for any theory with hidden variables. We explained this argument for the CHSH version of Bell’s inequality in a previous post. This CHSH correlation should not exceed a value of 2. Alain Aspect demonstrated that his entangled photons violate the Bell inequalities by a wide margin in all three experiments. He observed a CHSH correlation of almost 2.7 with minimal uncertainty (the standard deviation of his result was only 0.015).

The scientific community quickly recognized Aspect’s experiments for their impact. He was awarded the Holweck Medal, a European physics prize, in 1991, the Wolf Prize in Physics in 2010, and the Nobel Prize in 2022. Despite disproving Einstein’s statement that quantum mechanics is incomplete, he was awarded the Albert Einstein Medal in 2012.

The next post will discuss what sets quantum physics apart from other theories and why photons can establish these strong correlations. If you would like to read a more in-depth account of the work by John Bell and Alain Aspect, we can recommend the article by Olival Freire Junior [8]. In the meantime, we welcome your feedback in the comment section.

- A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, and N. Rosen, “can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete?” Phys. Rev. 47, 777 (1935).

- A. Aspect, P. Grangier and G. Roger, “Experimental Tests of Realistic Local Theories via Bell’s Theorem,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 460 (1981).

- A. Aspect, P. Grangier and G. Roger, “Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell’s Inequalities,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 91 (1982).

- Aspect, J. Dalibard and G. Roger, “Experimental Test of Bell’s Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1804 (1982).

- S. J. Freedman and J. F. Clauser, “Experimental Test of Local Hidden-Variable Theories,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 938 (1972).

- C. S. Wu and I. Shaknov, “The angular correlation of scattered annihilation radiation,” Phys. Rev. 77, 136 (1950).

- Obviously, it is an analogy; we do not have truly entangled ropes in the gym. Why we do not see macroscopic objects like ropes in an entangled state is an interesting question in itself.

- O. Freire Junior, “Alain Aspect’s experiments on Bell’s theorem: a turning point in the history of the research on the foundations of quantum mechanics,” Eur. Phys. J. D 76, 248 (2022).

Plaats een reactie