Many people (mainly physicists) consider physics the most fundamental field in science. These physicists may be in for a reality check. Nowadays, arguments from information theory are used as principles to explain fundamental properties of the quantum world. In this post, we explore the work of Marcin Pawłowski and co-workers. They use information theory to derive the boundary to quantum mechanical non-locality without the full quantum mechanical formalism [1].

In 1935, Albert Einstein started the debate on the completeness of quantum mechanics [2]. He argued that a complete theory must include ‘hidden variables’ to explain correlations between events coinciding in different locations. Fifty years later (in the 1980s), the science community had to accept (based on Alain Aspect’s Nobel Prize-winning experiments) that Nature is fundamentally non-local and that quantum mechanics gives a complete description without ‘hidden variables’ [3].

Parallel to work done by Alain Aspect, another insight emerged. In 1980, Boris Tsirelson published his analysis, which led to an upper limit to non-locality for quantum mechanics [4]. He used a metric that John Bell developed to mark the boundary between classical (local) theories and (non-local) quantum theory: The CHSH correlation [5]. In an earlier post, we introduced and applied the CHSH correlation to a coin game. Tsirelson used this CHSH correlation to quantify non-locality and derived an upper bound to non-locality from quantum mechanics.

- If the CHSH correlation does not exceed 2, we can explain the events with a theory based on local (maybe hidden) variables. We can explain the correlation through communication or information from a shared history.

- If the CHSH correlation is larger than 2 but not larger than 2√2, the correlation cannot be caused by local variables. Instead, we can use the non-locality of quantum mechanics to explain these correlations.

- If the CHSH correlation is between 2√2 and 4 we know that the non-locality needed to generate this correlation is stronger than what we can find in quantum mechanics. We would need a ‘superquantum’ theory to explain these correlations.

The value of 2√2 for the CHSH correlation is generally known as the Tsirelson bound. In their 1994 paper, Sandu Popescu and Daniel Rohrlich attempted to explain the Tsirelson bound from relativity theory [6]. Does the fact that information cannot travel faster than the speed of light explain why non-locality in quantum mechanics is limited by the Tsirelson bound (see our earlier post where we discussed this paper)? Popescu and Rohrlich showed that we could conceive many non-local theories that fully satisfy no-signaling but show stronger non-locality than what is allowed in quantum mechanics. In other words, our quantum mechanics is just one of many non-local theories fully compatible with relativity. Why, then, would Nature limit non-locality?

Marcin Pawłowski and co-workers imagined a situation where two parties share ‘resources’ with stronger entanglement than allowed by quantum mechanics [1, 7]. The two parties use these resources in combination with a ‘classical channel’ to share information. Information theory limits the amount of information the parties can transfer to the capacity of the classical channels. Pawłowski asked the question of whether entanglement beyond quantum mechanics would lead to a violation of the information theoretical limit. If this were the case, we could use information theory as a physical principle to derive the limitation to quantum mechanical non-locality.

Alice and Bob sharing a CD

In Pawłowski’s thought experiment, Alice has a CD with music. She thinks Bob would like the music but is unsure about his taste. She does know that Bob is very busy and will not spend more than a few minutes listening. Alice could send Bob the entire CD with all the songs. Bob could then select one song or listen to a short snippet of a few songs. As Bob can only spare a few minutes, this is very wasteful. Alternatively, Alice could select one song and send that to Bob, but she cannot know which song Bob would like best. In our world, this dilemma is not resolvable. Either Alice sends Bob all the information, or Alice makes a selection on behalf of Bob. In the first case, Bob selects which information he uses and dismisses the rest. In the second case, Bob has to accept whatever Alice has selected.

Now, imagine a world where Alice could share the data content of just one song so that Bob could decide which songs he received on the CD after receiving Alice’s message. In this case, Alice would send data that does not represent any of the songs (it would look like ‘random data’) but which Bob can manipulate to represent any of the songs on Alice’s CD.

Guessing game

Let us simplify the application. Imagine Alice has a string of 1s and 0s of length n (on Alice’s CD, the music is stored digitally as a sequence of 1s and 0s). Bob has the task of guessing a given value in Alice’s sequence. Beforehand, the sequence is unknown to Bob, and Alice does not know which of the values Bob has to guess. Alice can now communicate one bit of information to Bob (so she can send him either a ‘1’ or a ‘0’). After receiving this data from Alice, Bob can make his guess.

If, for this guessing game, Bob can correctly guess any value in Alice’s sequence after receiving one bit, we know that the ‘magic CD sharing’ application is possible. Bob can correctly guess any bit after receiving one bit, so he should be able to guess any sequence of m bits after receiving a message of m bits.

No-signalling boxes

We will give Alice and Bob a helping hand and allow them to share ‘no-signalling’ boxes. Sandu Popescu and Daniel Rohrlich proposed these NS boxes as devices showing the maximum possible CHSH correlation value [6]. We cannot look at what is inside these boxes, but we can describe their behavior in simple terms:

- NS boxes come in pairs; for each pair, one box is for Alice and one for Bob.

- Bob and Alice can each measure T or S (together, they measure TT, TS, ST, or SS. The first letter represents Alice’s, and the second is Bob’s choice).

- The answer they get is always 0 or 1 with 50% probability.

- The boxes are one-time-use; after a measurement, the box is disabled.

- A perfect box always gives Alice and Bob the same result, except when both measure T. In that case, they always get the opposite result.

- The k-value determines the probability that a box gives the perfect result; this probability is P(k) = (1/2) * (1 + k/4)

- For k = 4, the box is always perfect.

- For k = 0, the box is random (50% right answer, 50% wrong answer).

If one uses these NS boxes in a correlation experiment (for instance, Alain Aspect’s experiment), the CHSH correlation equals the k-value. So, the manufacturer of NS boxes with a k-value of two or lower could use local variables (in fact, these boxes would be perfectly feasible). Boxes with k-values up to 2√2 could be made from entangled particles. These boxes are, in principle, possible, but storing entangled photons in a box will lead to practical limitations. NS boxes with a k-value above 2√2 are hypothetical. These boxes are impossible in quantum mechanics as the correlation exceeds the Tsirelson bound. In a thought experiment, we are not limited by reality, so we can assume Alice and Bob have access to NS boxes of any k-value.

We imagine that Alice and Bob can order these boxes online (for instance, at Amazon) and store them in-house until needed. The manufacturer produced and shared the boxes well before Alice even thought of sharing a CD with Bob. The boxes do not contain any information on the CD Alice wants to share or the number that Bob has to guess.

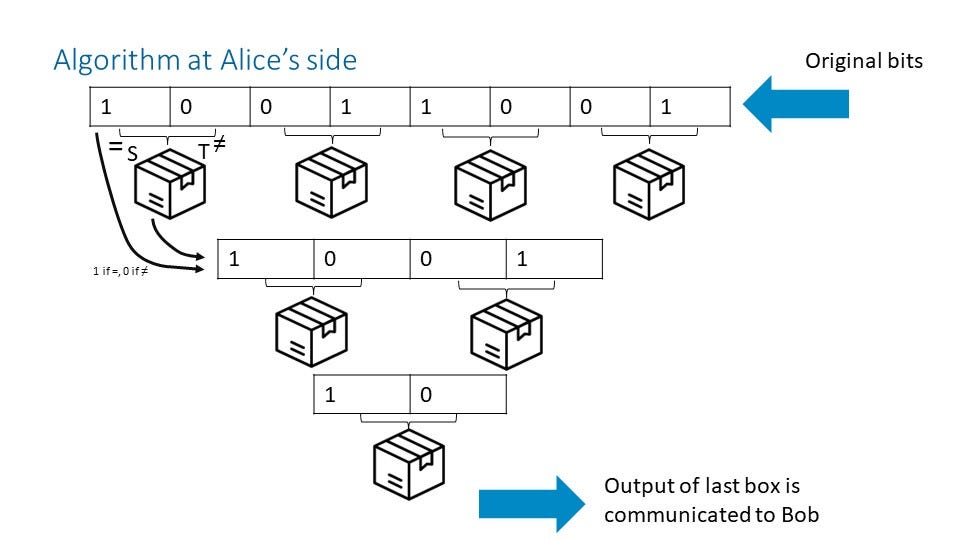

With a sufficiently large stock of boxes available, Alice can follow a protocol to generate the single bit she has to share with Bob. She starts with arranging one box for each pair of bits in her sequence (so if she has 8 bits, as in the example, she uses four boxes in the first step). She will generate a new sequence from these 8 bits and four boxes, this time for 4 bits and two boxes. She will repeat the first step on that sequence to generate a sequence of 2 bits. On those two bits, she repeats the first step (this time with a single box) to generate the bit she shares with Bob. For every box, Alice measures S if the two corresponding bits are equal and T if they differ. If the measurement result is the same as the first bit, Alice notes a ‘1’ in the output sequence; if the result differs from the first bit, she notes a ‘0’. Alice repeats this logic for all boxes.

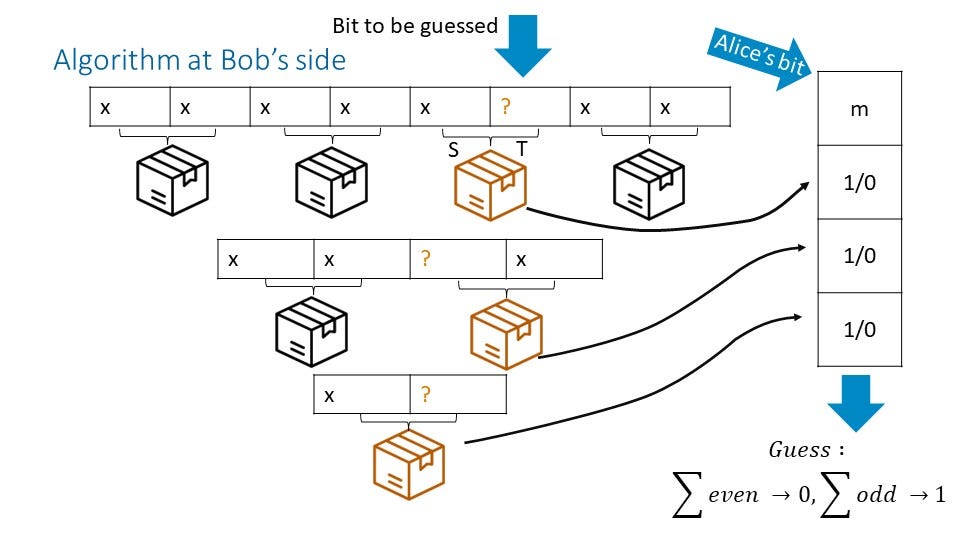

Bob arranges his boxes in the same ‘triangle’ as used by Alice. NS boxes are paired, so Alice and Bob must use the same order. For the first step, he arranges the first four boxes for the eight possible positions. In this example, Bob will guess the value of the 6th bit in Alice’s sequence. He has to perform the T measurement on the 3rd box and note the result. Then, in the next step, he arranges two boxes and performs the S measurement on the second box. His final measurement is T for the last box. Bob now has three measurement results and the bit he received from Alice. If there is an even number of 1s in these four bits, his guess is zero; if there is an odd number of 1s, he will guess one.

Python simulation

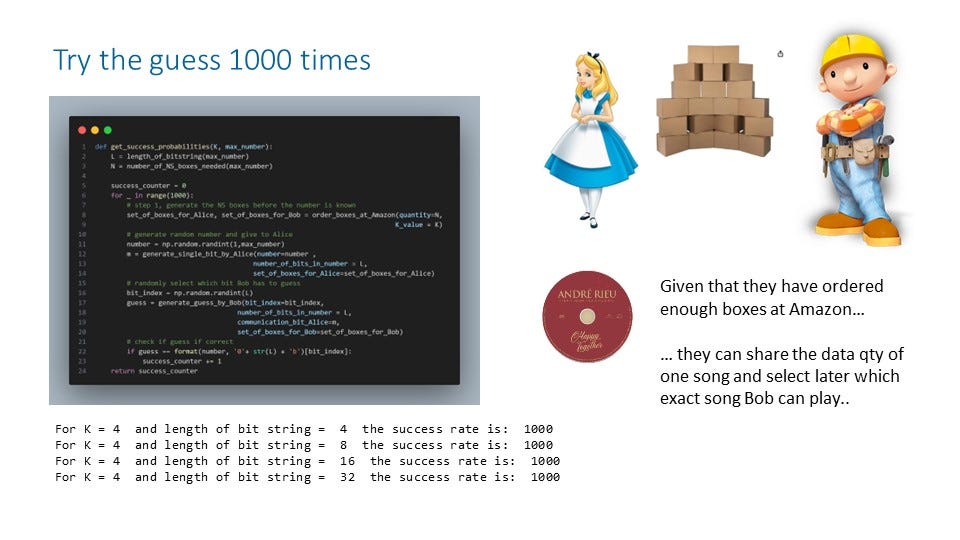

The algorithms used by Bob and Alice are tedious but straightforward. We implemented these algorithms in Python to demonstrate the result. For the complete code, see GitHub.

In our code, we generate the NS boxes by calling the function `order_boxes_at_Amazon()`.

order_boxes_at_Amazon(quantity=N, K_value = K)

This will generate a set of boxes for Alice and a set of boxes for Bob. Then, we generate the bit string for Alice from a random number in binary form.

number = np.random.randint(1,max_number)

The actions at Alice’s are captured in the function `generate_single_bit_by_Alice()`, which generates the communication bit.

generate_single_bit_by_Alice(number=number ,

number_of_bits_in_number = L,

set_of_boxes_for_Alice=set_of_boxes_for_Alice)

The function `generate_guess_by_Bob()` captures the actions taken by Bob to come to the guess bit. The bit_index Bob has to guess we generate as a random number.

bit_index = np.random.randint(L)

generate_guess_by_Bob(bit_index=bit_index,

number_of_bits_in_number = L,

communication_bit_Alice=m,

set_of_boxes_for_Bob=set_of_boxes_for_Bob)

We can put these actions together and execute the thought experiment several times. In the code snippet below, we run 1000 trials of this experiment for a string of 8 bits at Alice’s side. We use boxes with a k-value of 4. We see that in all trials, Bob is able to guess the bit successfully! So, one bit of classical communication is enough for Bob to guess any bit in Alice’s sequence with a 100% success rate.

K = 4

max_number = 100

L = length_of_bitstring(max_number)

N = number_of_NS_boxes_needed(max_number)

success_counter = 0

for _ in range(1000):

# step 1, generate the NS boxes before the number is known

set_of_boxes_for_Alice, set_of_boxes_for_Bob = order_boxes_at_Amazon(

quantity=N,

K_value = K

)

# generate random number and give to Alice

number = np.random.randint(1,max_number)

m = generate_single_bit_by_Alice(

number=number ,

number_of_bits_in_number = L,

set_of_boxes_for_Alice=set_of_boxes_for_Alice

)

# randomly select which bit Bob has to guess

bit_index = np.random.randint(L)

guess = generate_guess_by_Bob(

bit_index=bit_index,

number_of_bits_in_number = L,

communication_bit_Alice=m,

set_of_boxes_for_Bob=set_of_boxes_for_Bob

)

# check if guess if correct

if guess == format(number, '0'+ str(L) + 'b')[bit_index]:

success_counter += 1

# print the success rate for 1000 tries

print('For K =', K, ' and length of bit string = ', L,' \

the success rate is: ', success_counter)

The result is:

For K = 4 and length of bit string = 8 the success rate is: 1000

We can repeat this experiment for larger bit sequences on Alice’s side. In all cases, Bob has a 100% success rate in guessing the number.

Conclusion

Alice and Bob need a sufficient stack of no-signalling boxes of perfect quality (k-value 4). With that, Bob can be 100% successful in guessing any bit from a sequence at Alice’s side, even though only one bit can be communicated. It is important to remember that the NS boxes are produced and distributed before Alice’s random number is generated, and Bob chooses which bit in Alice’s sequence he wants to guess. So, the NS boxes cannot contain any relevant information. The non-local correlation between the boxes enables information sharing, but the boxes themselves do not serve as a communication channel.

To have a 100% success rate in the guessing game or to access all songs on Alice’s CD, Bob needs to have access to more information than is shared with him by Alice through the classical channel. Information theory teaches that information cannot appear out of nowhere. So, Bob’s success rate clearly violates the principles of information theory. NS boxes with a high k-value do not violate relativity theory or causality. Within physics, no higher-level axiom or principle would ‘forbid’ these boxes to exist. Still, we know that quantum theory does not enable these correlations. The insight from Pawłowski and co-workers is that we have to look outside physics to identify higher-level principles that explain why Nature does not provide unlimited non-locality.

In our next post, we go a step further. We study what happens if we use boxes with a k-value lower than 4 (i.e., ‘imperfect’ boxes). We especially look at what happens if the k-value drops below the Tsirelson bound. How high is Bob’s success rate when using NS boxes of a quality level allowed in quantum mechanics? Would the performance still violate information theory? Please leave your comments and builds in the section below this post.

[1] M. Pawłowski, T. Paterek, D. Kaszlikowski, V. Scarani, A. Winter and M. Zukowski, “Information causality as a physical principle,” Nature 461, 1101 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08400

[2] A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, and N. Rosen, “Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete?” Phys. Rev. 47, 777 (1935).

[3] A. Aspect, P. Grangier, and G. Roger, “Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell’s Inequalities,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 91 (1982).

[4] B. Tsirelson, “Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality,” Letters in Mathematical Physics 4, 93, (1980).

[5] J. F. Clauser, M. A. Horne, A. Shimony, and B. A. Holt, “Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories” Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880 (1969).

[6] S. Popescu and D. Rohrlich, “Quantum Non-locality as an Axiom,” Foundations of Physics 24, 397 (1994).

[7] M. Pawlowski and V. Scarani, “Information causality,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1112.1142

Plaats een reactie